LOUP SARION „Saliva“ 12 March – 16 April 2022

Saliva

“Brassaï: In the lower strata of the valley of Les Eyzies, excavation archaeologists had the brilliant idea of preserving a cross-section four to five meters high, with layers built up over millennia. It’s like a mille-feuille.

Picasso: And you know what’s responsible? It’s dust! The earth doesn’t have a housekeeper to do the dusting. And the dust that falls on it every day remains there. Everything that’s come down to us from the past has been conserved by dust.”—Pablo Picasso to Brassaï[1]

“It’s just dirt, really.”—Peter Schlesinger[2]

. . .

Brassaï’s “mille-feuille,” Picasso’s phantom duster: such stratification is a leitmotif in Loup Sarion’s two new parallel bodies of work in Saliva, of architectonic resin panel reliefs, and nose forms sculptured in beeswax.

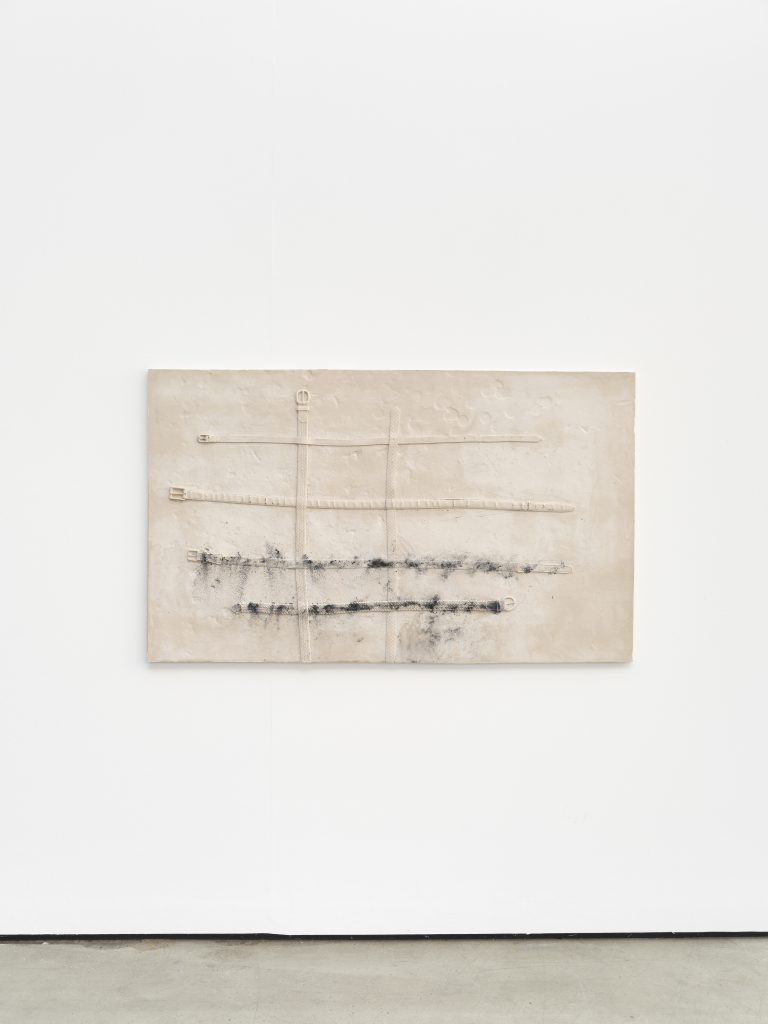

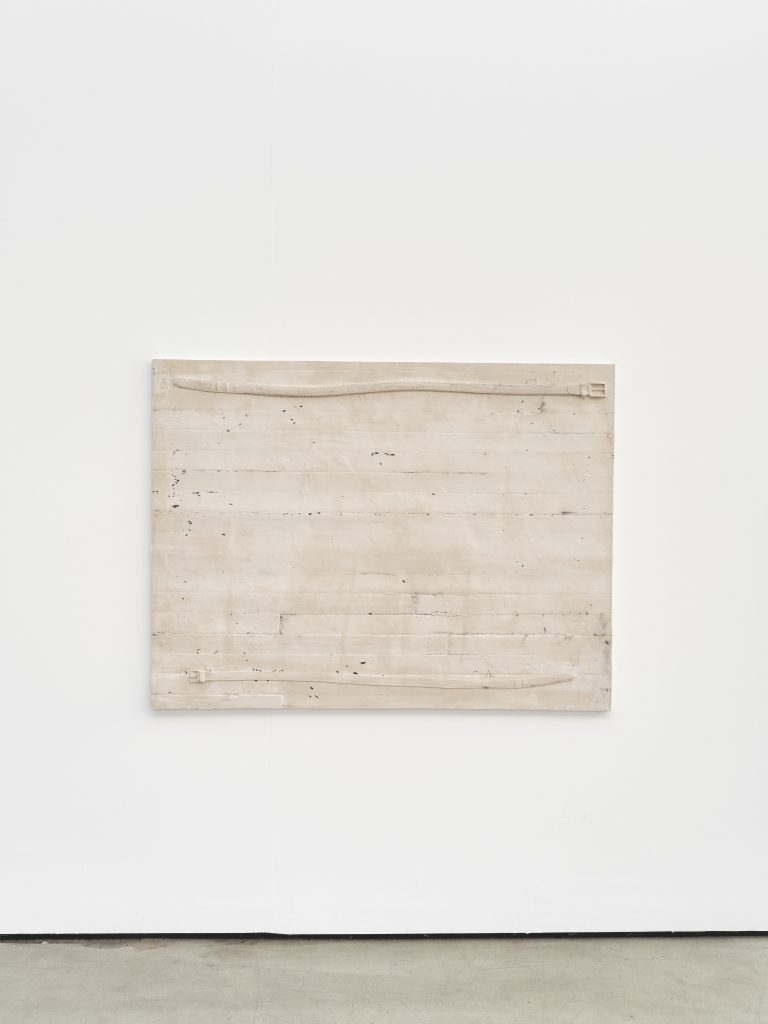

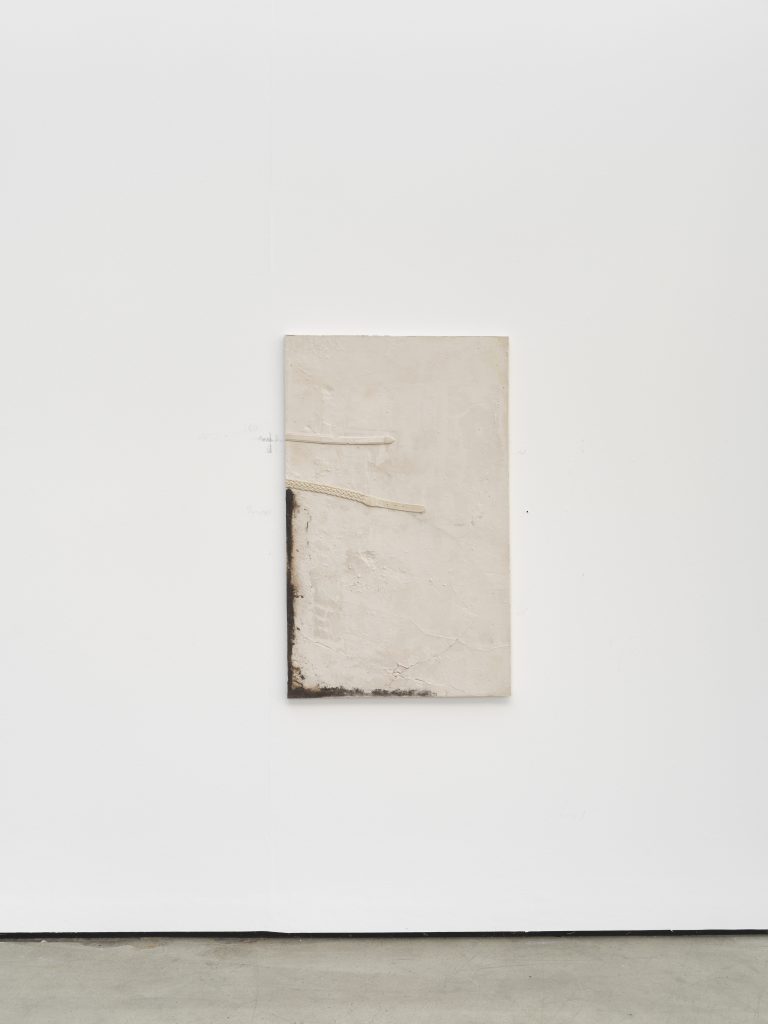

Sarion’s panels’ sedimentations—his “mille-feuille”—are not so much of timescale, though, but of site and species of skin. Composites and complex infoldings, in part, of fissure and cupule-filled walls of his studio, and floors of his apartment, his panel casts, via the molds that mothered them, migrate lived architectures in Bushwick, Brooklyn, to neutraler ones in Cologne. As if skin tissue being grafted, they clothe gallery walls in sudden synthetic material fictions of an epidermal kind of urban Palaeolithic, which, in feeling, share something of the inevitability and drama of a fossil’s sedimentary re-emergence as readymade relief. What was first floor is now wall—not that such axes hold, as in caves, which are simply volumes wrought by water. Spatialities of uninterrupted geological fabric.

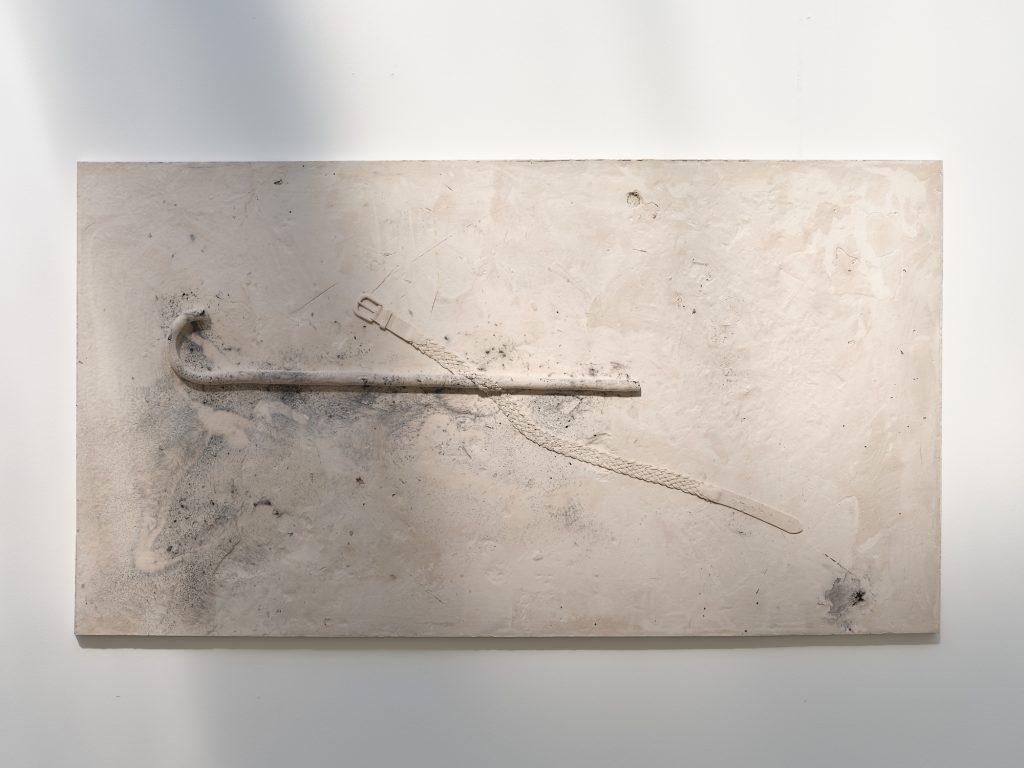

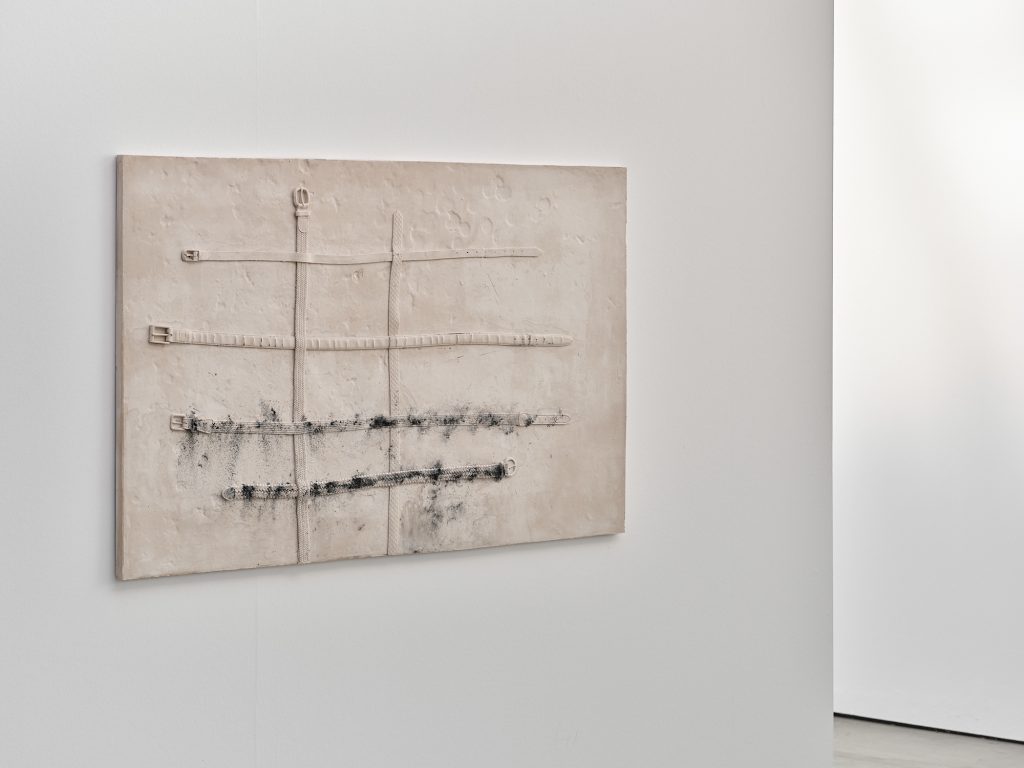

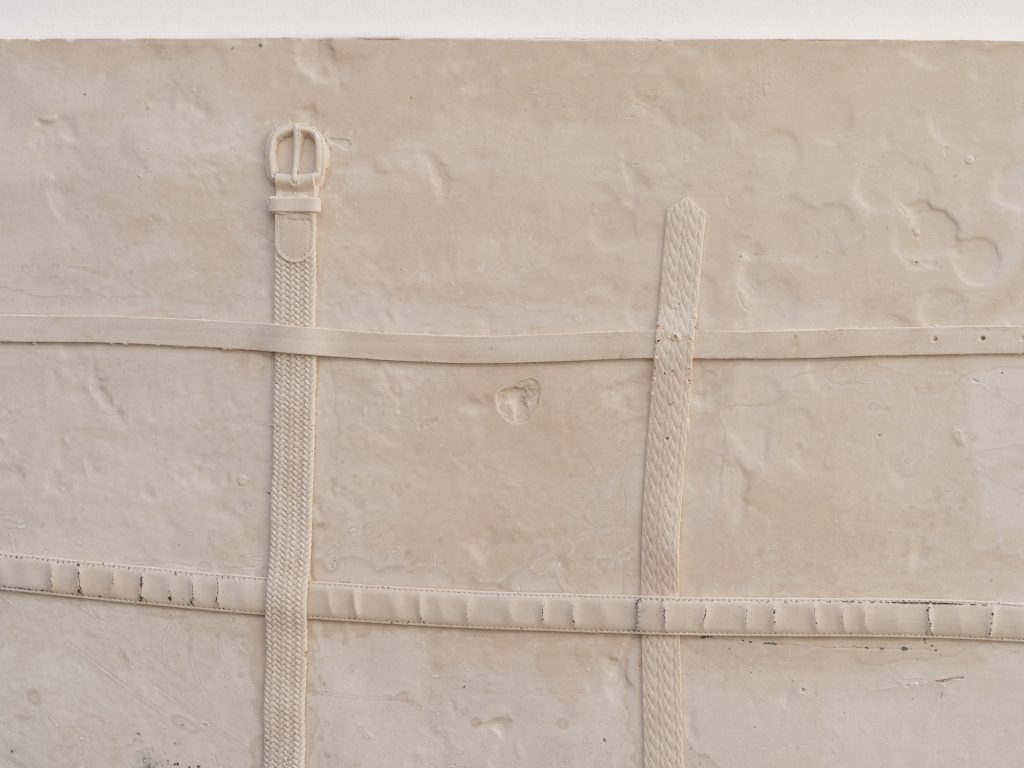

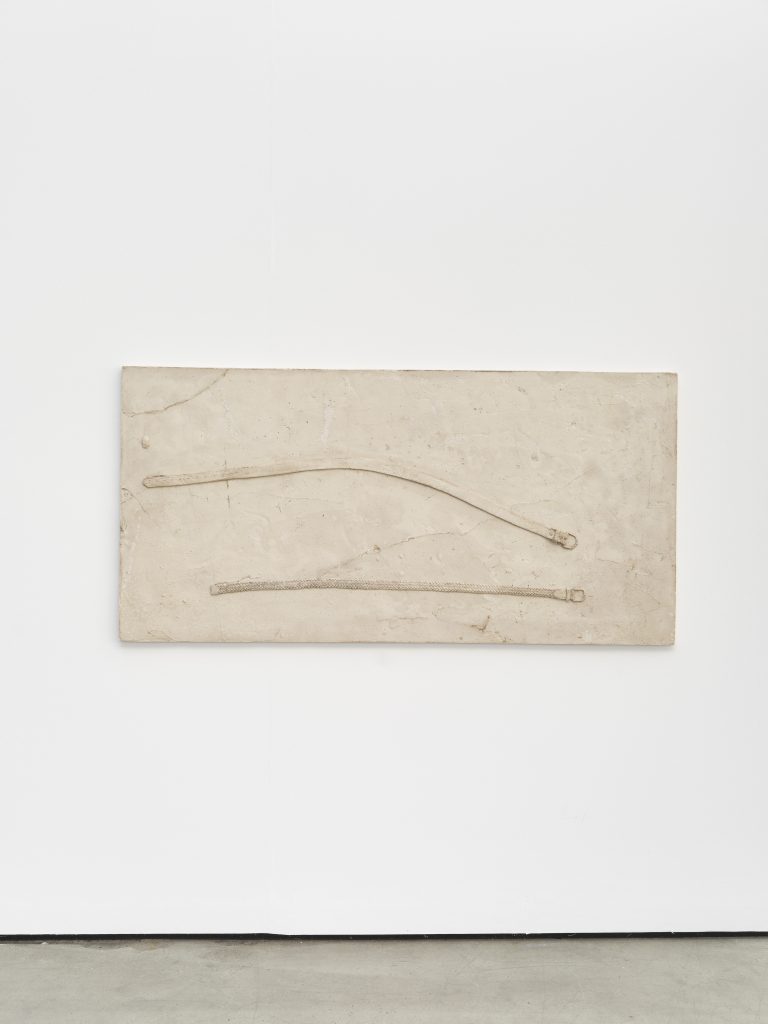

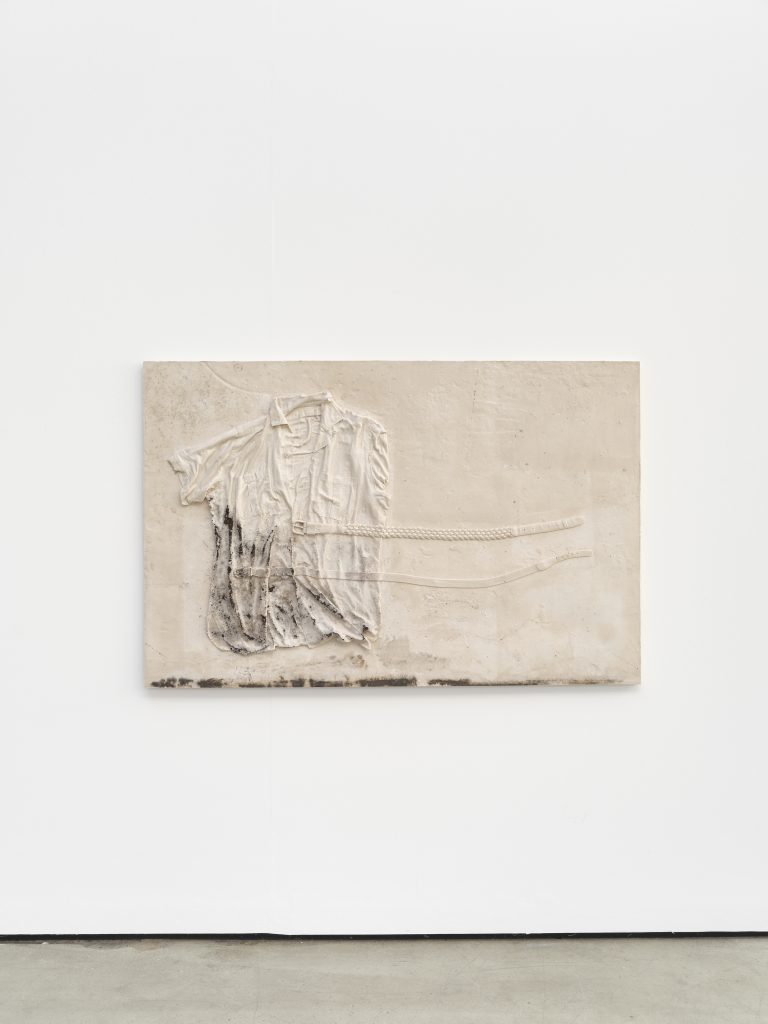

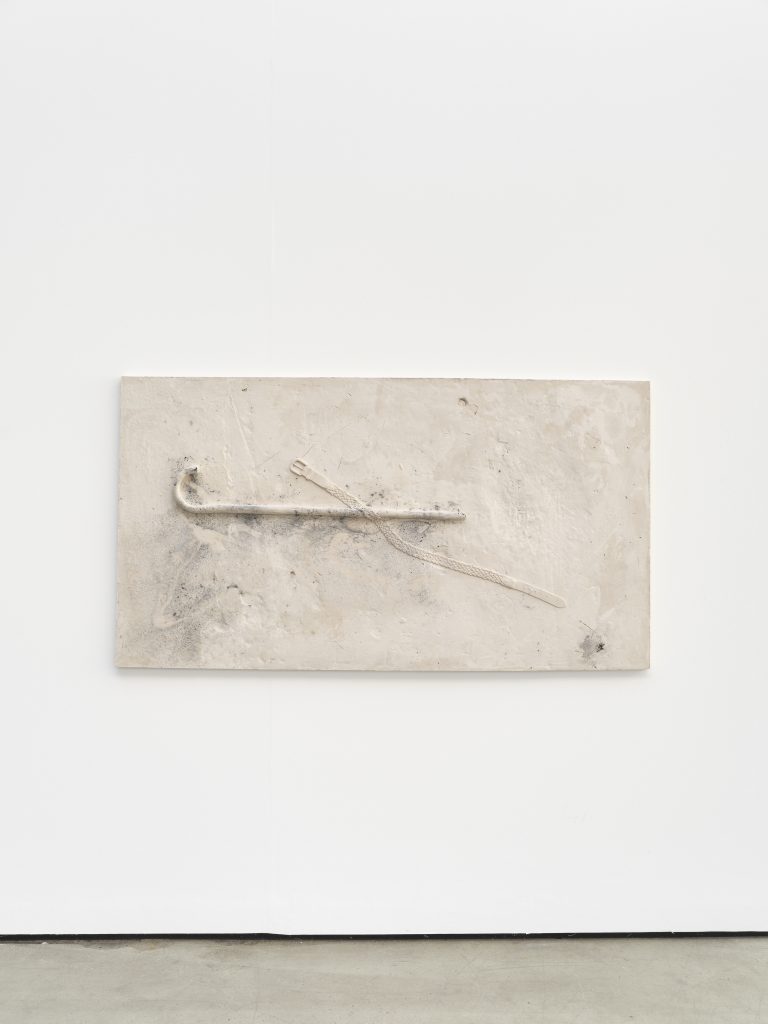

Here, casts molt city surfaces, turning hide in their unpeeling, and into which real dust—like white noise—paints itself, by itself, in particle heap. An aesthetics of the nano: specs of black floor paint, rust flecks from a belt. Even sheen endures its translation from negative to positive. One thinks of Heidi Bucher’s “skinnings,” of interior architectures coated in latex and then stripped, rendered entire, except Sarion makes stranger, chimeric figurations; ones that move further from their sources. His are haptic, but unfaithful facsimiles—and in their playful imaging of fabric and occasional frottage-applied pigment, whether charcoal or metal dust, more like Pati Hill’s xeroxes than indexical molds.

Leather belts, mostly sidewalk foraged, their skin still legible as such; walking canes, always sensory prostheses and spatial stethoscopes that “see” for us. A shirt, uncannily soft even in newfound solid form, though note its loose soil hem. These layerings have their origin in his and any’s lovers’ clothes’ own entwinings—the hasty undress in the kitchen, the strewing—inadvertent mapmaking reencountered as chance logic mornings after. As casts of molds that themselves “kissed” walls, Sarion’s panels are love letters of a mille-feuille kind. Of an eros of the imprint.

Nose extrusions, in counterpoint, perform a prosthetic kiss of remote sensing—as aerial, olfactive “tongues,” and mouths for molecules, whose machinations remain occluded from view. They insist, sotto voce, that unmoldable anatomical cavities are the lived architectures that give us to sense, to wish to touch, to want to mold, in the first place. Urges that exceed origin.

Emma McCormick-Goodhart x Bureau Eponym

New

York City, March 2022

[1] Brassaï, Conversations with Picasso, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Chicago: Univesity of Chicago Press, 1999).

[2] Alex Needham, “In the Studio With Peter Schlesinger, Creative Legend,” W Magazine, January 14, 2022.