JENS KOTHE

„Element System“

June 7 – July 6, 2019

Text by Carina Bukuts scroll downwards

German Text

Das Maß der Dinge

Carina Bukuts

Den Prozess der Globalisierung bezeichnen viele als Nivellierung. Ein Modus, in dem Universalität zwischen verschiedensten Kulturen entstehen kann – beispielsweise in Form eines Einheitsmaßes. Orientierte sich der Großteil der Weltbevölkerung bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts an eigenen, nationalen und regionalen Maßeinheiten, sollte sich das mit der Festlegung des Meters bald ändern und dadurch den Welthandel nachhaltig beeinflussen. In mitten der französischen Revolution wurden die Astronomen Jean Delambre und Pierre Méchain daher ausgesandt, um die Erde zu vermessen und aus den Daten eine neue Maßeinheit abzuleiten: genau der zehnmillionste Teil zwischen Nordpol und Äquator sollte den Meter definieren. Wenig später nachdem dieser als internationales Längenmaß eingeführt wurde, stellte sich jedoch heraus, dass den Astronomen in ihren Berechnungen ein Fehler unterlaufen ist. Um 0,2 Millimeter verfehlten sie die exakte Distanz zwischen Äquator und Nordpol. Es überrascht daher kaum, dass der Architekt Le Corbusier den Meter für ungeeignet hielt und stattdessen eine eigene Maßeinheit entwickelte, namentlich den Modulor. Während er dem Meter Willkür unterstellte, sollte der Modulor sich an menschlichen Proportionen orientieren und dadurch die Architektur und Städte, in denen wir leben maßgeblich beeinflussen.

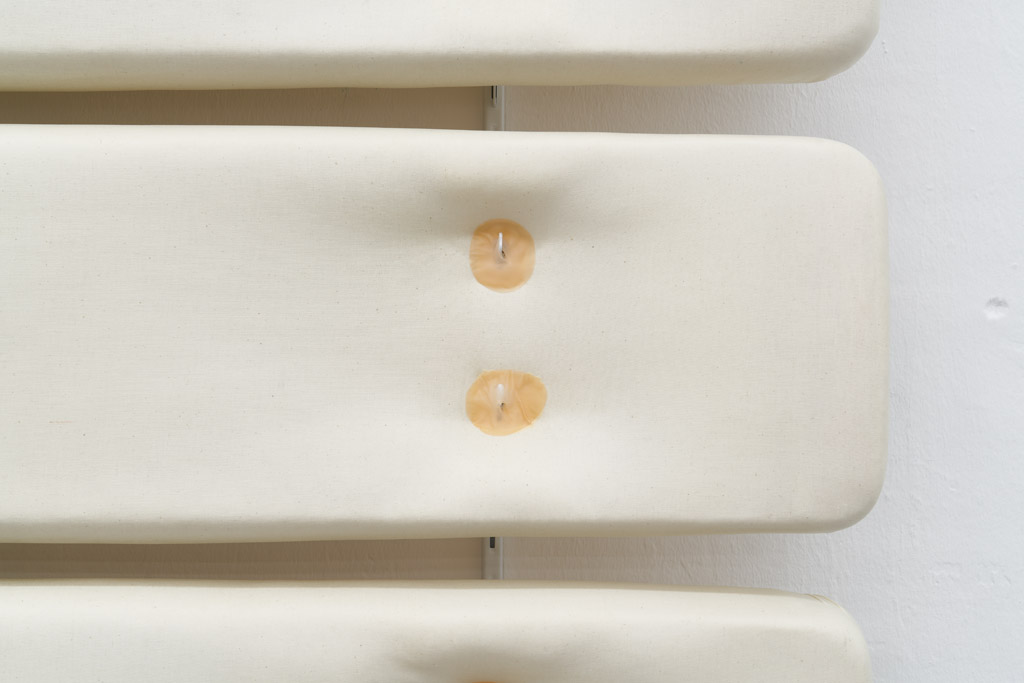

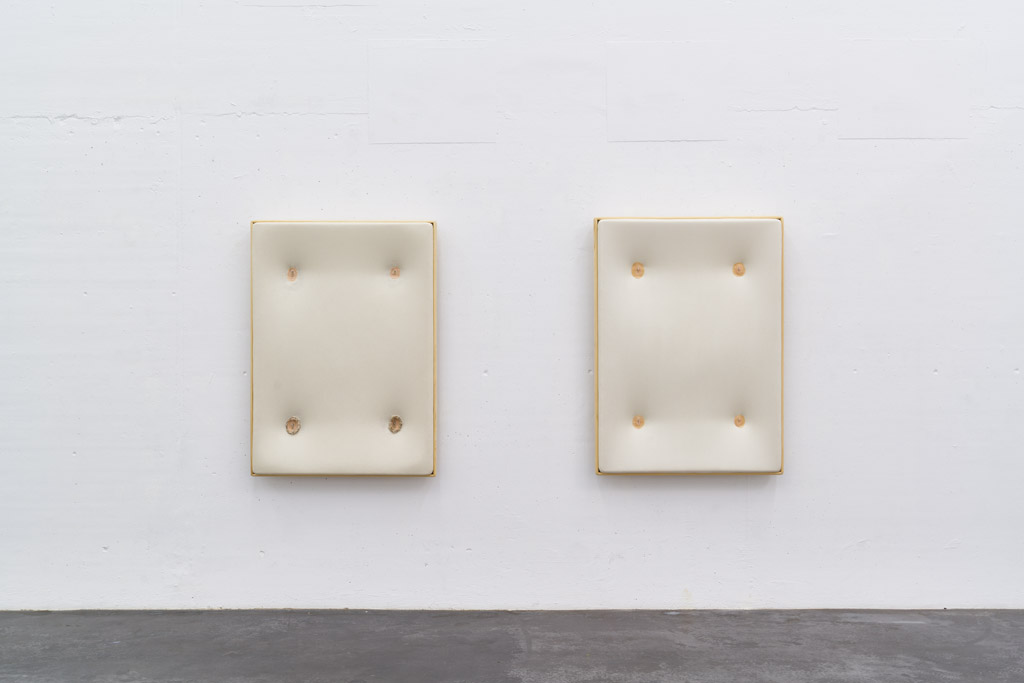

Jens Kothes Ausstellung „Element System“ in der Berthold Pott Galerie ist genau von dieser Dualität zwischen Körper und Norm gekennzeichnet. Obgleich es keine Bestrebung zur Etablierung einer Maßeinheit gibt, hat Kothe für die Ausstellung ein modulares System entwickelt, das unter Umständen sehr wohl als ein solches funktionieren könnte. O.T. Elemsys I (2019) besteht aus zwölf Einheiten aus hellem Nesselstoff, die alle jeweils das gleiche Volumen aufweisen. In der Galerie sind die einzelnen Module mithilfe einer Hängevorrichtung übereinander gereiht, sodass sich ihre horizontale Ausrichtung in die Vertikale zieht und dadurch im Gesamtbild an Paneele erinnert. Während diese Anordnung sich auf die Raumdimensionen der Galerieräume bezieht, ist die Installation als solches vielfältig variabel. Die Systematik, die dieser Arbeit zugrunde liegt, erinnert an modulare Bauweisen aus der Architektur, die insbesondere aufgrund ihrer Flexibilität und Effizienz vor allem beim Sozialwohnungsbau des 20. Jahrhunderts verwendet wurden. Das bekannteste Beispiel führt zurück zu Le Corbusier mit der Unité d’Habitation, die er gleich für mehrere europäische Großstädte in Serienproduktion gab. Doch die strenge Systematik von Le Corbusier ist nicht zwingend der gemeinsame Nenner mit den Arbeiten Kothes – vielmehr ist es der Bezug zum menschlichen Körper.

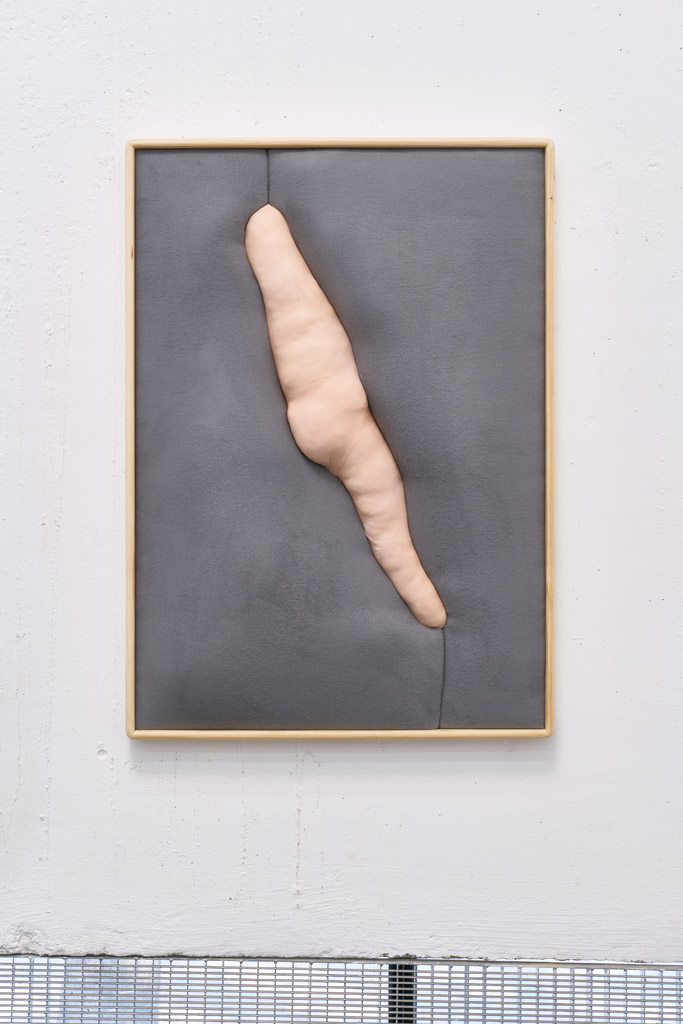

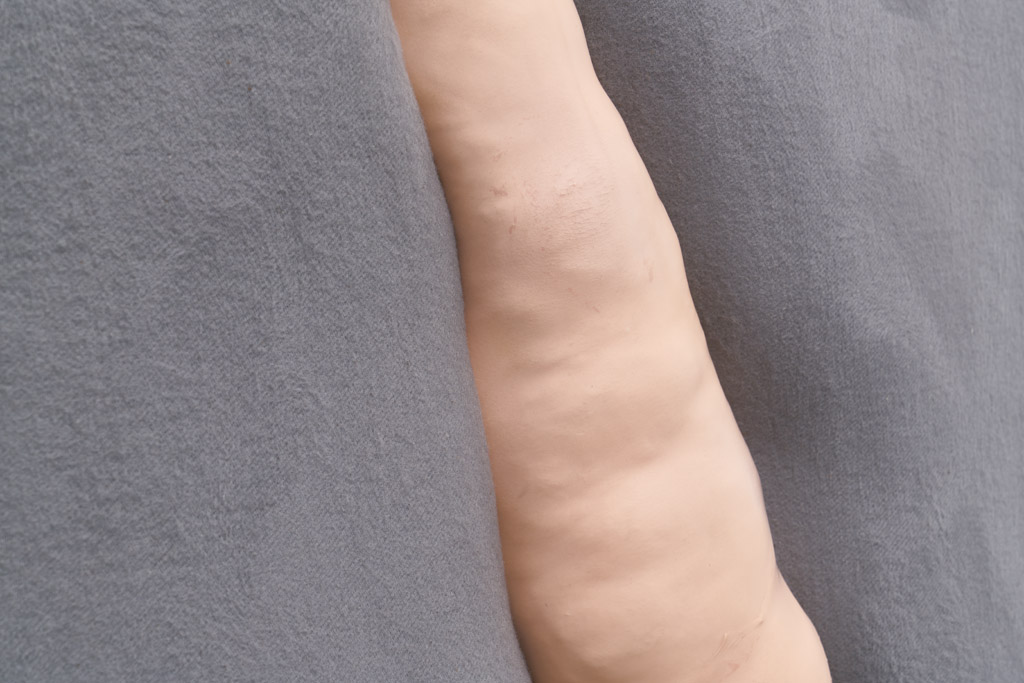

Mit seinen interior-ähnlichen Arbeiten triggert Kothe nämlich immerzu ein taktiles Begehren beim Betrachter. Stärker als bei Elemsys I zeigt sich dies in den Bänken, die den gesamten Ausstellungsraum einnehmen. Doch im Gegensatz zu der Vorlage aus dem Museum, die zum Verweilen einlädt, wird dem müden Körper bei benches (2019) der Platz verweigert. Es darf nur mit den Augen getastet werden. Auf jeweils zwei filigranen Holzbeinen lasten schwere Mörtelsitzflächen, in denen unterschiedlich große Aussparungen vorgenommen worden sind. In diese hat Kothe diverse Formen aus aufgepolstertem Latex eingepasst, die an Vergrößerungen von Hautpartikeln oder gar ganze Hautlappen erinnern. Besticht hier die eindeutige visuelle Referenz zum menschlichen Körper, lösen die eingearbeitete Watte und das Kunstfell in bench IV (2019) noch stärker den Wunsch nach einer taktilen Erfahrung aus. Zusätzlich ist über der Wattepolsterung ein gelbes Netz gespannt. Ähnlich wie ein Netzhemd die Muskulatur des Oberkörpers betont anstatt sie zu verschleiern, verstärkt der Einsatz der Netzstruktur hier in gleicher Weise das Volumen der Skulptur.

Es ist diese Kombination unterschiedlicher Materialeigenschaften die in „Element System“ ein Spannungsverhältnis erzeugt, das zwischen Härte und Weiche, zwischen Organischem und Industriellem changiert und damit den menschlichen Körper inmitten dieser Gegensätze verortet. Doch dieser Zustand birgt auch das Potential mehr zu sein als das Ringen um dieser beiden entgegengesetzten Kräfte: „Consider: There is no division of humanity into strong and weak halves, protective/protected, dominant/submissive, owner/chattel, active/passive. In fact, the whole tendency to dualism that pervades human thinking may be found to be lessened, changed.”1Ursula Le Guin schlägt eine vollständige Aufhebung von menschgemachten Dualismen vor und vielleicht braucht es diese erst, um wirklich wissen zu können, was das Maß der Dinge ist. Bis dahin hat Jens Kothe hingegen eine Praxis entwickelt, die Justus Köhnckes Idee von „weichen Zäunen“ wohl am nächsten kommt: einem Nivellieren von Antagonismen.

Kurz-Biography JENS KOTHE:

Geboren 1985, lebt und arbeitet in Bochum, Deutschland, 2013-17: Meisterklasse Andreas Gursky, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, 2009-2011: Staatliche Bildhauereischule, Oberammergau, 2007-09: TU Dortmund, Architektur. Ausgewählte Ausstellungen: Jens Kothe, Pfirsich, Köln (2019), „On intimacy“ RFK, Düsseldorf (group, 2019), „Insane in the membrane“ Philara Collection, Düsseldorf (group, 2018), „Towards a theory of powerful things“ Rod Barton, London (group, 2018), „Die Grosse“ Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf (group, 2018), „Jens Kothe“ Hyperraum E.V. Bochum (solo, 2017), „Jens Kothe“ Kunsthalle Bochum (solo, 2017), Ruhrtriennale Bochum (group, 2015), „En el Castillo“ Museo Internacional de Arte Contemporaneo, Spanien (group, 2014) //

English Text

The Shape of Things

Carina Bukuts

Many call the process of globalization levelling. A mode in which universality between different cultures can arise – for instance in the form of a standardized measure. While the majority of the world’s population oriented themselves to their own, national and regional units of measurement until the end of the 18th century, this soon changed with the definition of the meter and thus had a lasting influence on the world trade. In the middle of the French Revolution, astronomers Jean Delambre and Pierre Méchain were therefore sent out to measure the earth and to derive a new unit of measurement from the data: exactly the ten millionth part between the North Pole and the equator was to define the meter. Shortly after the meter was introduced as an international measure of length, however, it turned out that the astronomers had made a mistake in their calculations. They missed the exact distance between the equator and the North Pole by 0.2 millimetres. It is therefore hardly surprising that architect Le Corbusier considered the meter unsuitable and instead developed his own unit of measurement, namely the Modulor. While he accused the meter of arbitrariness, the Modulor was supposed to be oriented towards human proportions and thus have a decisive influence on the architecture and cities in which we live.

Jens Kothe’s exhibition ‘Element System’ at Berthold Pott Gallery is characterized exactly by this duality between body and norm. Although there is no attempt to establish a unit of measurement, Kothe has developed a modular system for the exhibition that could very well function as such. O.T. Elemsys I (2019) consists of twelve units of light nettle fabric, each with the same volume. In the gallery, the individual modules are stacked on top of each other using a suspension device, so their horizontal orientation stretches into the vertical and is thus reminiscent of panels. While this arrangement refers to the spatial dimensions of the gallery space, the installation as such is versatile. The system on which this work is based recalls modular architectural construction methods, which were mainly used in 20th century social housing models due to their flexibility and efficiency. The best-known example leads back to Le Corbusier with the Unité d’Habitation, which he gave in series production for several major European cities. But Le Corbusier’s strict systematic approach is not necessarily the common denominator with Kothe’s works – it is rather the reference to the human body.

With his interior-like works, Kothe constantly triggers a tactile desire in the viewer. Stronger than in Elemsys I, this can be seen in the benches that occupy the entire exhibition space. But in contrast to the original from the museum, which invites the viewer to rest, benches (2019) rejects the tired body. It may only be explored with the eyes. Heavy mortar seats, in which cut-outs of varying sizes have been made, weigh on two delicate wooden legs. Kothe has fitted various upholstered latex forms into these, recalling enlargements of skin particles or even entire skin flaps. While the clear visual reference to the human body is captivating here, the integrated cotton wool and artificial furs in bench IV (2019) provoke an even stronger desire for a tactile experience. In addition, a yellow net is stretched over the cotton padding. Similar to a mesh shirt, which emphasizes the muscles of the torso instead of concealing them, the use of the mesh structure here also enforces the volume of the sculpture.

It is precisely this combination of different material qualities that creates a tension in “Element System” which oscillates between hardness and softness, between the organic and the industrial, locating the human body in the midst of these contrasts. But this state also bears the potential to be more than the struggle between these two opposing forces: “Consider: There is no division of humanity into strong and weak halves, protective/protected, dominant/submissive, owner/chattel, active/passive. In fact, the whole tendency to dualism that pervades human thinking may be found to be lessened, changed.”[1] Ursula Le Guin proposes a complete abolition of man-made dualisms, and perhaps this is what it takes to really know what the measure and shape of things are. Until then, Jens Kothe has developed a practice that probably comes closest to Justus Köhncke’s idea of ‘soft fences’: a levelling of antagonisms.

[1] Ursula Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969

Short Biography JENS KOTHE:

Born 1985, lives and works in Bochum, Germany, 2013-17: masterclass of Andreas Gursky, Academy Düsseldorf, 2009-2011: National Sculptor School, Oberammergau, 2007-09: TU Dortmund, Architecture. Selected Exhibitions: Jens Kothe at Pfirsich, Cologne (2019), „On intimacy“ at RFK, Düsseldorf (group, 2019), „Insane in the membrane“ at Philara Collection, Düsseldorf (group, 2018), „Towards a theory of powerful things“ at Rod Barton, London (group, 2018), „Die Grosse“ at Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf (group, 2018), „Jens Kothe“ at Hyperraum E.V. Bochum (solo, 2017), „Jens Kothe“ at Kunsthalle Bochum (solo, 2017), Ruhrtriennale Bochum (group, 2015), „En el Castillo“ at Museo Internacional de Arte Contemporaneo, Spain (group, 2014) //