AGATA INGARDEN

„Hot House“

March 14 – April 03, 2019

Installation Views (for the text by Oriane Durand scroll downwards)

Exhibition text English (for German version scroll downwards)

Agata Ingarden combines, superimposes, connects and interweaves various types of materials in abstract sculptures that simultaneously evoke concrete forms. The vocabulary associated with her works refers to living organisms, plants, as well as technology. In various sizes, her sculptures hang either on the walls like sensor screens, from the ceiling like metal lianas, at the ends of which caramelised onions trickle down, or lie on the floor as strange vehicles, a combination of sledge and spaceship. The latter type, which is presented in this exhibition, consists of a large metal structure, drawn by a pair of mirrors in the form of fluttering hearts, driven by a machine composed of an arrangement of rods, caramel balls and a concretion of oysters. Spaceships, generators, sensor screens or insect machines camouflaged behind colours that artificially imitate nature – together, these sculptures set a narration in motion which explores the connection between humankind, nature and technology.

This narration takes form starting from the choice of materials and their treatment. The materials are ostensibly subjected to only a few modifications. They are often presented in a rough state, at times painted in a full colour and connected by gestures associated with elementary mechanics. The metal rods are rudimentarily welded together to form a geometric framework with visible joints. The wood is presented in its natural state or processed in a block to give back to it the schematic aspect of a branch. Connected at its end, the elements wood and metal seem to form some parts of a body. Both caramel and oysters are fused into an amorphous aggregate, without any fixed form or true unity. From this original state of matter, the obvious work of the hand and the scientific aspect of this work, a vision emerges directly out of the past of our future. A leap into an archaeo-futuristic universe that combines surrealism and alchemy.

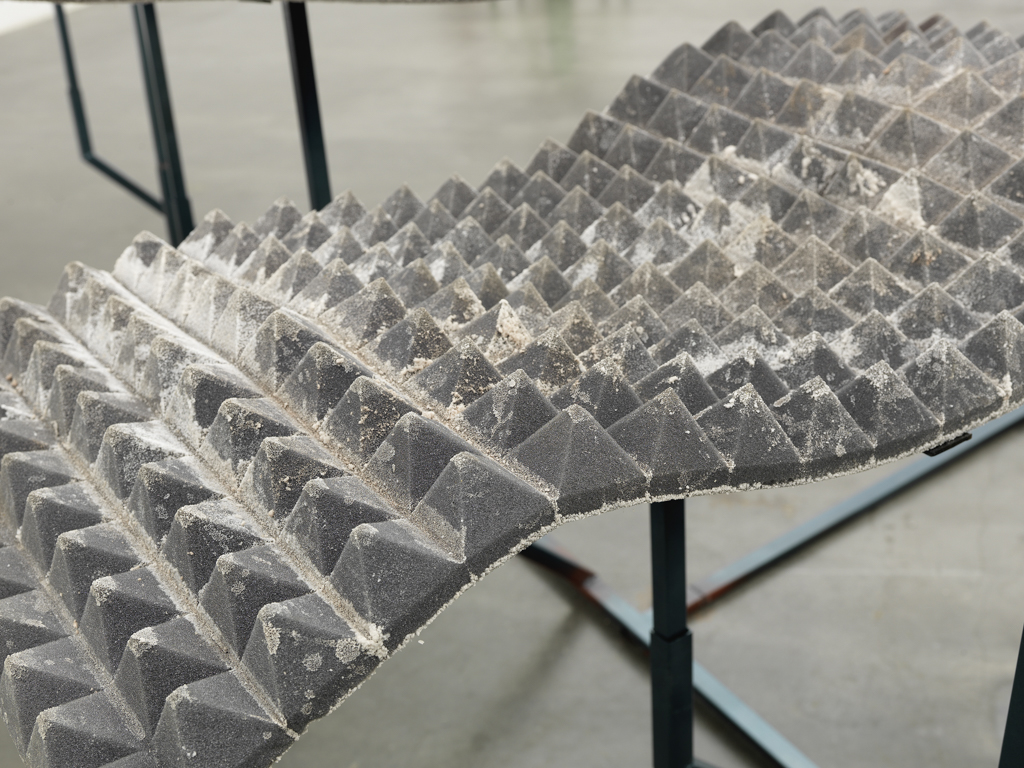

Like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), these sculptures occasionally even resemble creatures from elsewhere, whose ‘component parts might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.’[1] Some works actually seem to be permeated by activity. This happens when the caramel comes into contact with the air and a certain temperature. Modified by oxygen, it changes from a solid to a liquid state. It drips down onto the surrounding surfaces like a life fluid. This is reflected on a more metaphorical level in the use of acoustic foam, which absorbs the sound and waves that surround it. With each movement of the viewer, the mirrors reflect something new. Through these subtle but incessant changes, the sculpture becomes transformed over time. Beyond the fact that it adopts forms of life, it seems to manifest the energy that flows actively between materials and their environment.

At the core of Ingarden’s critical analysis, the concept of energy plays a fundamental role in her work. Irrespective of whether it lies in the mutation experienced by caramel, or is simply evoked it, it recalls the ideas of transformation reminiscent of those of entropy. Entropy ‘is the last and most mysterious of the five physical quantities (temperature, pressure, volume, internal energy, entropy) that represent the state of a thermodynamic system, i.e. a limited set of materials capable of exchanging heat and working with the external environment.’[2] But whereas, for Robert Smithson (1938–1973), entropy also corresponds to the irreversible collapse of things and the ‘energy is more easily lost than obtained, and that in the ultimate future the whole universe will burn out and be transformed into an all-encompassing sameness’,[3] it is not understood by Ingarden as something that necessarily leads to deterioration. Following the ideas of New Materialism, Ingarden regards matter as something active, whether animate or not, and perceives this energy as something that mutually interlinks the bodies. By leading us out into an environment in which nature and technology are fully interconnected and the boundary between the living and the non-living is fluid, the artist ultimately poses the question as to the influence of things and materials on humankind: How could the perception of this change our relationship to the world?

Oriane Durand

Brief biography: Agata Ingarden, born in Kraków/Poland in 1994; studied at Beaux-Arts de Paris (2013-18) and Cooper Union, New York (2016). Solo exhibitions: 2018 – Piktogram, Warsaw; Sans-Titre, Paris / 2019 – Soft Opening, London (Jan./Feb.); Berthold Pott, Cologne (March/April); Liste Basel, with Piktogram Warsaw (June) / Group exhibitions: 2019 – Dash, Kortrijk/Belgium; Michel Journiac, Paris.

Exhibition text German:

Agata Ingarden kombiniert, überlagert, verbindet und verwebt verschiedene Arten von Materialien in abstrakten Skulpturen, die gleichzeitig konkrete Formen evozieren. Das mit ihren Arbeiten assoziierte Vokabular bezieht sich sowohl auf das Lebendige, das Gewachsene, als auch auf das Technische. In verschiedenen Größen hängen ihre Skulpturen entweder wie Sensorbildschirme an den Wänden, wie Metall-Lianen an der Decke, an deren Ende „Karamell-Zwiebeln“ versickern oder entfalten sich auf dem Boden als fremdartiges Fahrzeug, eine Kombination aus Schlitten und Raumschiff. Letzteres, das in dieser Ausstellung präsentiert wird, besteht aus einer großen Metallstruktur, gezogen von einem Gespann aus Spiegeln in Form flatternder Herzen, angetrieben durch ein an eine Maschine erinnerndes Objekt, komponiert aus Stäben, Karamellkugeln und einer kegelförmigen Komposition aus Austern. Raumschiffe, Generatoren, Sensorschirme oder Maschinen-Insekt, getarnt hinter Farben, die die Natur künstlich imitieren – gemeinsam setzen diese Skulpturen eine Narration in Gang, die die Verbindung zwischen Mensch, Natur und Technologie auslotet.

Diese Narration nimmt aufgrund Ingardens Materialauswahl und ihres Umgangs damit Gestalt an. Anscheinend unterliegen die Materialien nur wenigen Änderungen. Sie werden häufig im rauen Zustand gezeigt, manchmal monochrom bemalt und durch Gesten miteinander verbunden, die zu einer elementaren Mechanik gehören. Die Metallstäbe sind rudimentär miteinander verschweißt, um ein geometrisches Gerippe mit sichtbaren Gelenken zu bilden. Das Holz wird in seinem natürlichen Zustand präsentiert oder im Block bearbeitet, um schematische Aspekte des Astes zu pointieren. An ihren Enden miteinander verbunden, scheinen die Elemente Holz und Metall bestimmte Teile eines Körpers zu bilden. Sowohl Karamell als auch Austern werden zu einem amorphen Aggregat verschmolzen, ohne festgelegte Form oder wahre Einheit. Aus diesem ursprünglichen Zustand der Materie, der offensichtlichen Arbeit der Hand und dem wissenschaftlichen Aspekt ihrer Arbeit, entsteht eine Vision aus der Vergangenheit unserer Zukunft. Ein Sprung in ein archäo-futuristisches Universum, das Surrealismus und Alchemie vereint.

Wie bei Mary Shelleys Frankenstein (1818) ähneln diese Skulpturen manchmal sogar Kreaturen von anderswo, deren „component parts might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth „[1]. Einige Arbeiten scheinen tatsächlich von einer Aktivität durchdrungen zu sein. Diese wird offenbar, wenn das Karamell mit der Luft und einer bestimmten Temperatur in Berührung kommt: Durch Sauerstoff modifiziert, geht es von einem festen in einen flüssigen Zustand über. Es tröpfelt auf die darunter liegenden Oberflächen wie eine „Flüssigkeit des Lebens“ herab. Auf metaphorischere Weise spiegelt sich dies in der Verwendung von Akustikschaum, auf den das Karamell tropft, wider, der den Klang und die Wellen, die ihn umgeben, absorbiert. Bei den in den Skulpturen zu findenden Spiegeln reflektiert sich mit jeder Bewegung des Betrachters etwas Neues. Durch diese subtilen, aber unaufhörlichen Veränderungen, verwandelt sich die Skulptur im Laufe der Zeit. Über die Tatsache hinaus, dass Ingardens Skulpturen an gewisse Lebensformen erinnern, scheinen sie die Energie zu bekunden, die aktiv zwischen Materialien und ihre Umgebung fließt.

Im Zentrum der Fragestellung der Künstlerin spielt der Begriff der Energie eine grundlegende Rolle. Unabhängig davon, ob sie in der Mutation, die das Karamell erfährt, liegt, oder sie einfach nur hervorgerufen wird, beschwört sie die Ideen der Transformation, die an die der Entropie erinnern. Entropie „ist die letzte und geheimnisvollste der fünf physikalischen Größen (Temperatur, Druck, Volumen, innere Energie, Entropie), die den Zustand eines thermodynamischen Systems, d. h. ein begrenztes Materialset beschreibt, das in der Lage ist, Wärme auszutauschen und mit der Außenumgebung zu arbeiten »[2]. Wenn aber für Robert Smithson (1938-1973) Entropie auch dem irreversiblen Zusammenbruch der Dinge entspricht und die „energy is more easily lost than obtained, and that in the ultimate future the whole universe will burn out and be transformed into an all-encompassing sameness »[3], wird sie nicht von Ingarden als etwas begriffen, das notwendigerweise zur Verschlechterung führt. Den Ideen des Neuen Materialismus folgend, betrachtet Ingarden die Materie als aktiv, sei sie belebt oder nicht, und nimmt diese Energie als etwas wahr, das die Körper in einer Wechselbeziehung miteinander verbindet. In dem uns die Künstlerin in eine Umgebung hinausführt, in der Natur und Technologie völlig miteinander verbunden sind und die Grenze zwischen der lebendigen und der nicht lebendigen fließend ist, stellt sie schließlich die Frage nach dem Einfluss von Dingen und Materialien auf den Menschen: Wie könnte dessen Wahrnehmung unsere Beziehung zur Welt verändern?

Oriane Durand

Brief biography: Agata Ingarden, born in Kraków/Poland in 1994; studied at Beaux-Arts de Paris (2013-18) and Cooper Union, New York (2016). Solo exhibitions: 2018 – Piktogram, Warsaw; Sans-Titre, Paris / 2019 – Soft Opening, London (Jan./Feb.); Berthold Pott, Cologne (March/April); Liste Basel, with Piktogram Warsaw (June) / Group exhibitions: 2019 – Dash, Kortrijk/Belgium; Michel Journiac, Paris.